Reflective Statement

The process of managing a blog and presenting academic research here has proven challenging. Motivated to create egalitarian graphic art, conveying the character and flaws of analog media in a digital context, I chose the keyword “Humanity”, which seemed to link to both. Academic articles about a range of relevant issues – from theological morality to computer-generated emotion – have been interesting to read, and provided visual prompts, but can’t define what “Humanity” might be.

As such, I’ve struggled to reconcile this research process with the need to produce coherent creative outcomes for Practice 1, sensing something of clear value in my enquiry, but not knowing quite what. In truth, I’ve at times wished that a these theories, theses and analyses would seep into my subconscious and infuse my creative work. …But although it’s challenging to find a direct correlation between the musings of Sartre and my design skillset, I have rationalised certain Situationist concepts, including the Society of the Spectacle, relative to my Practice 1 proposals.

In terms of using this research to inform practice, it’s been valuable to learn more about graphicacy and semiotics, and I’m particularly drawn to employing pictograms in my designs, having recognised their similarity to historic representations of humanity in Paleolithic art. Indeed, the excitement of seeing such connections for the first time – between academic theories and practice, or discrete areas of creative practice – constitutes the most rewarding part of a research project such as this; thus it was revelatory to me that cave paintings might be viewed as public art, and in some respects may not be so different from modern representations of humanity in shop windows and on road signs.

Perhaps the most surprising connection I’ve found is between glitch art and analog media, their potential for interaction offering a new dynamic for attempts to bring humanity’s imperfections into the digital realm. Without taking my own embryonic findings into a tutorial discussion, I wouldn’t have thought to explore this area, and this not only underlines the value of allowing research methods to spontaneously change direction, but of the free-thinking interaction of humans: it’s as if appreciating a spark within human-to-human communication offers a key insight into humanity’s condition, which, of course, only confirms Mark Pagel’s position, as reported on this blog.

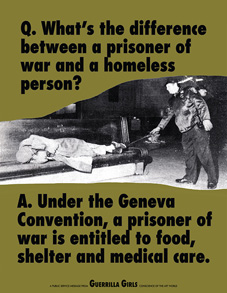

Prominent within my practice-linked research have been the triumvirate subjects of anti-consumerism, analog media and public art, each equating with aspects of “Humanity” in my mind. However, there was no strategy beyond starting with graphic artists referenced in SAT1, and, at some point, focusing on how image and typography (predominantly analog) is used by contemporary practitioners, specifically within graphic art installations and exhibitions; even then I found it enlightening to detour via the work of Sister Corita Kent.

While I didn’t plan a non-linear approach to this research, on reflection, I see that a certain unevenness often pervades my work, despite intentions to impose a structure. Sometimes this is problematic, but it can create the conditions for unexpectedly positive outcomes, and, in the context of researching a multi-faceted subject like “Humanity”, may be appropriate, even representing it to some degree: diverse, unpredictable, making significant mistakes along the way but, hopefully, having a potential for good.